Arya Kshema Spring Dharma Teachings:

17th Gyalwang Karmapa on The Life of the Eighth Karmapa Mikyö Dorje

March 14, 2021

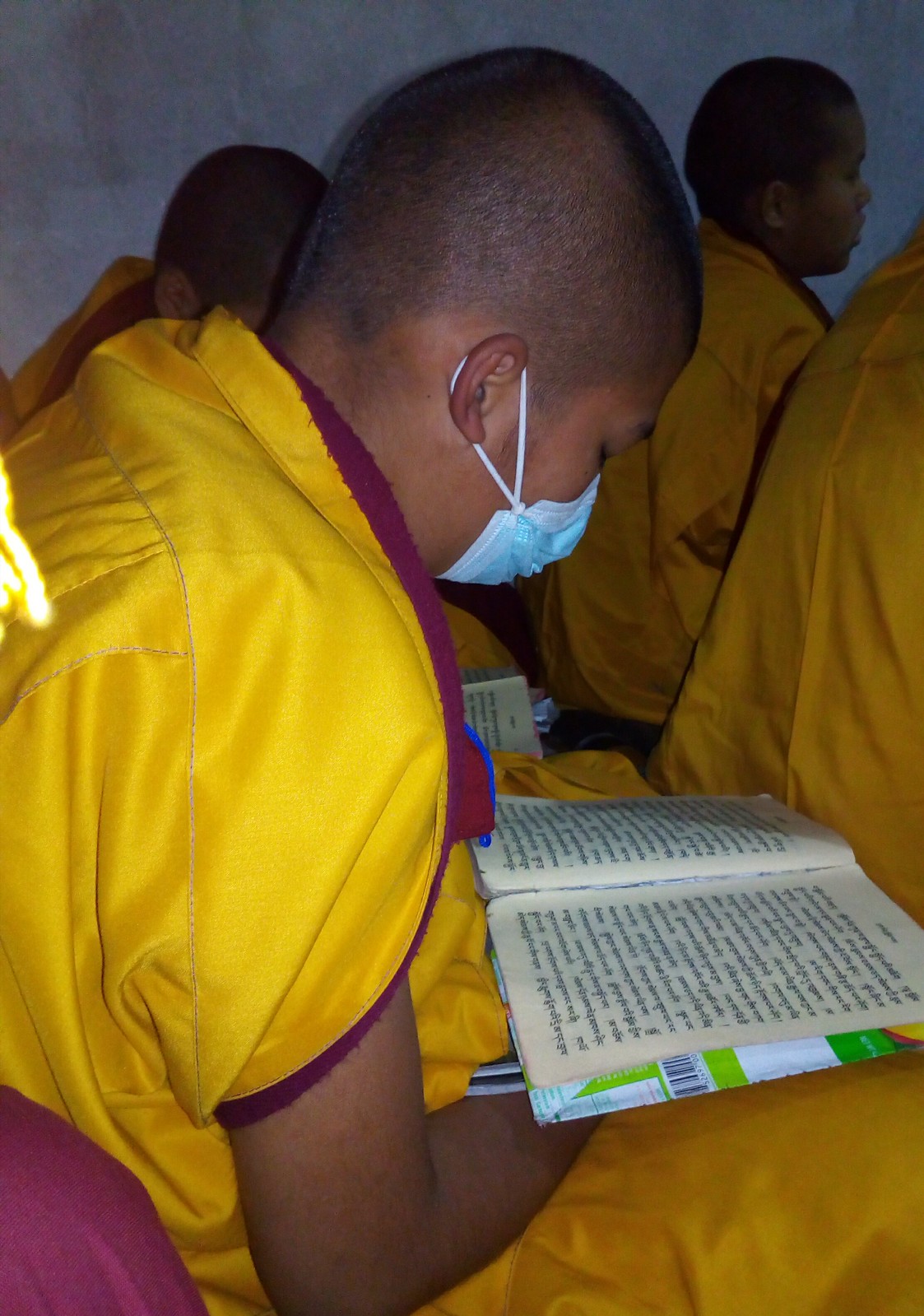

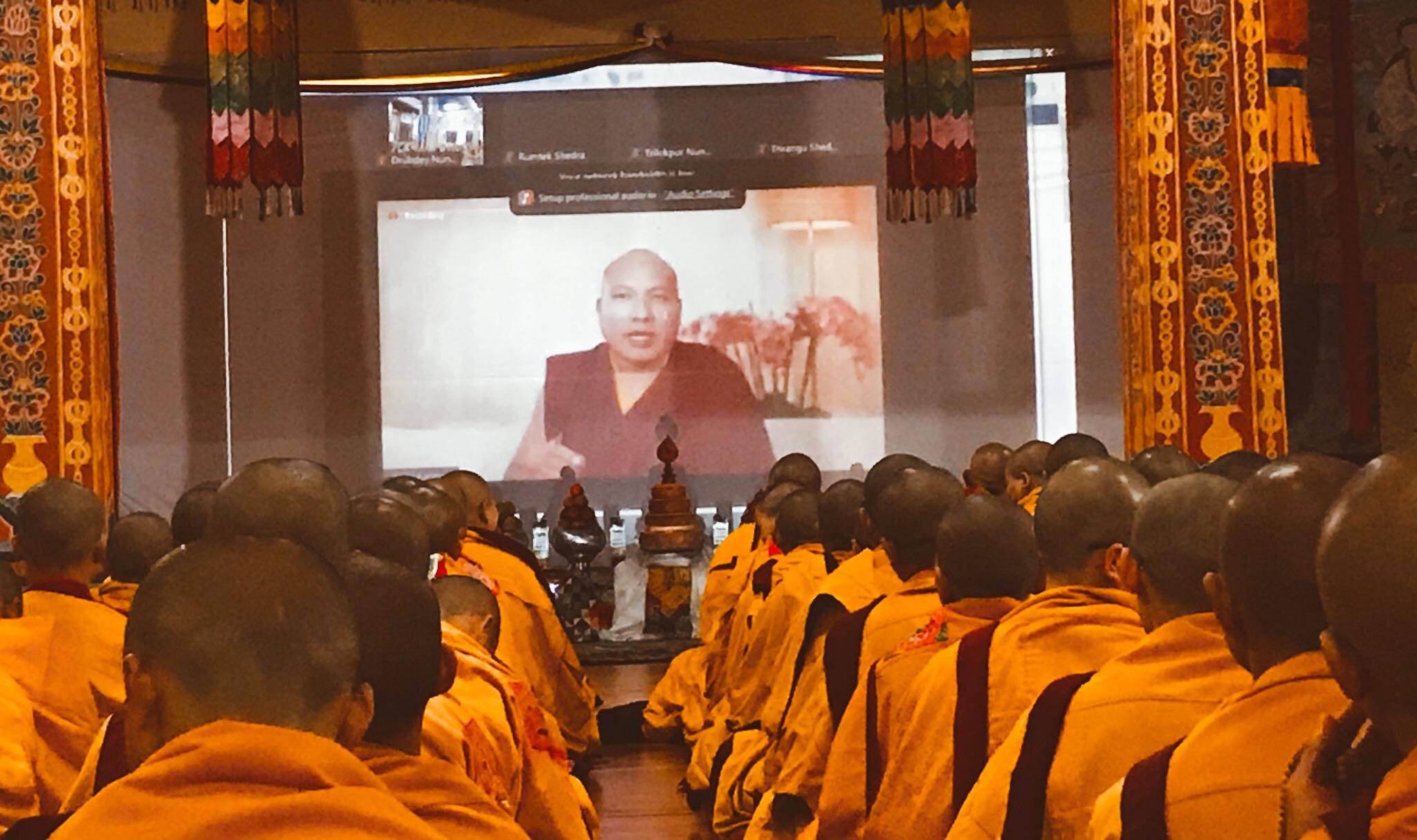

After offering prayers, His Holiness sincerely welcomed Kyabje Bokar Rinpoche Chungsi, Khenpo Rinpoche, all of the khenpos, geshes, and teachers and all the monks. In particular, His Holiness greeted the nuns in the nuns’ shedras as well as all the male and female lay students watching the webcast around the world.

Part One: All Sentient Beings are as Kind as Our Parents

His Holiness began the eighteenth day of teachings by returning to Mikyö Dorje’s Good Deeds. He reminded us that the text is into two main parts and the ninth verse falls within the second part: The main part: how he practiced the paths of the three types of individuals. This second part is comprised of three parts: 1) How he practiced the path of the lesser individual, 2) How he practiced the path of the middling individual, and 3) How he practiced the path of greater individual.

Within the third section on practicing the path of the greater individual, there are three additional topics. The last topic is how he practiced the path of the greater individual which includes: a) the intention: rousing bodhichitta, b) the action: meditating on the two types of bodhichitta, and c) how he trained in the precepts of the two types of bodhichitta. Verse nine reads:

All beings, without distinction, are the same as my parents.

It is illogical to group them into factions of friend and foe.

With uncontrived love for beings in intolerable states,

I thought, when can I bring them the benefit of true enlightenment?

I think of this as one of my good deeds.

His Holiness proceeded to provide a more in-depth explanation of the intention to rouse bodhicitta. First, he explained that we all say we are Buddhist and call ourselves Mahayana or Vajrayana practitioners. We identify ourselves as Buddhist, wear the clothes, and so forth; however, when it comes to the actual practice, do we actually act as a practitioner should? On the one hand, if a friend experiences a loss or something inauspicious happens, then we worry and feel miserable for them. On the other hand, if something goes well for people who are against us, then we cannot bear it; we think to ourselves that it should not go that well for them.

His Holiness emphasized that we forget about having love and affection for all sentient beings. We consider anyone we do not like as our enemy. Even if we have something good to say about them, we cannot even bring ourselves to do it. When we think this way, it is impossible to have love and compassion for all sentient beings.

To truly bring any amount of benefit, we have to turn our thinking inward. It is imperative we examine our thoughts and ourselves. Before we do any Dharma practice, we have to analyze and check if our intention and our motivation aligns with the Dharma. Only then we can understand what we have in our hearts, and we have to examine this to decide what actions we need to take or what to give up.

Mikyö Dorje’s life exemplifies what it truly means to rouse bodhichitta, as he always acted with love and compassion. His Holiness emphasized, “From the bottom of his heart, he thought of all sentient beings as his kind parents; that is how he acted and thought.” His Holiness proceeded with several examples: Whenever Mikyö Dorje saw any sentient being committing the cause of suffering by performing misdeeds, he could not bear it, and everyone could see his worry. From the moment Mikyö Dorje heard of anyone stricken by illness, bad crops, famine, armed conflict resulting in death, masters and disciples not getting along, and so forth, it was as if he experienced the situation and any of these difficulties himself. His Holiness emphatically shared, “He felt that suffering. He would always ask what could he do?”

During Mikyö Dorje’s lifetime, in Ütsang each lord or minor king’s responsibility included protecting everyone in the region. To illustrate his worry and concern for these well-known leaders and gurus who had bad intentions and conduct, Mikyö Dorje would say: “What they should do is to protect many people, but the way they think and act ignores helping all others. In the next life, which lower realm will they fall into?’”

His Holiness continued:

Mikyö Dorje would say, ‘You are harming your own everlasting aims. When the sky has fallen without you noticing, what point is there to any other meaningless concerns?’ This is a sign of how he worried that the other person would be permanently unhappy.

Mikyö Dorje always had the pure intention to cherish others and never forgot that all sentient beings had been his parents. While we have to intentionally strive for this intention, it automatically arose in his mind; it was something he never had to strive to produce. He lived this through his teaching. For instance, after a relative died someone came to ask Mikyö Dorje, “’What virtuous action should I do on their behalf?’ And, he would reply, ‘If you have so much love and compassion for the deceased, shouldn’t you love all beings who have been your parents?’”

His Holiness emphasized several key points that demonstrated how Mikyö Dorje roused bodhichitta. He never differentiated between who was helpful or harmful, friend or foe; he recognized that we have known all sentient beings through countless rebirths. Mikyö Dorje exhibited this by not having any bias as he wanted everyone to do well and to be equally happy. His intention was evident in how Mikyö Dorje interacted with anyone who came to speak with him, for he never had the idea he was close to some and not to others. He was happy with whatever work anyone did for him. He was very easy to serve. The attendants and the workers of the encampment would do the jobs they were given. He would not criticize. Sometimes people made mistakes but he would not embarrass them in front of others. He would speak of them lovingly and that influenced everyone in his entourage.

The reason for this is evident from the time Mikyö Dorje received bodhisattva vows from Sangye Nyenpa Denma Druptop Rinpoche. At that time Sangye Nyenpa said to him, “’I have the feeling that for innumerable past lives, your bodhichitta has not weakened.’” Sangye Nyenpa’s comment is surprising since he did not flatter people. As a mahasiddhi and a yogi, he used only very direct, forceful speech. His Holiness pointed out that if we look at the way Sangye Nyenpa spoke, it is immediately clear that Mikyö Dorje had deep imprints of bodhichitta from previous lifetimes.

Whether Mikyö Dorje was writing, reading, studying, teaching, giving transmissions of Dharma, or making connections with others through mani mantras, he would make a pure intention. For this reason, people placed high hopes in him as he was free from any selfish thoughts or intentions. His Holiness noted:

From the time he was little, he would say, “Now, I have this title of Karmapa. I do not have any hope of being a great lama or an influential person in this lifetime just because I have been given the title of Karmapa. Because of this title, I have become a Lord of Dharma or great lama, and, because of that, innumerable people have placed great hopes in me and depend on me. To benefit those people and to tame their mind streams, just knowing how to teach a short text, knowing how to give them a short instruction, or doing a few years or months of meditation retreat will not lead to anything. The beings to tame are infinite and the afflictions are infinite. So, I also need infinite methods for taming beings. I need to train myself in listening, contemplating, and meditating to benefit them.” He said this from the time he was very young.

He was never distracted when he had to take a lot of empowerments and transmissions. He followed the main four great teachers. He took responsibility himself to read great texts. He always spent his time listening, contemplating, and meditating on the scriptures. When he gained a bit of understanding, he was as delighted as if he had found a jewel in a garbage heap. If he did not quite understand something, he would say,

“I am an obscured being deprived of true Dharma!” He would worry and suffer so much that his health was disturbed and he could not sleep at night. However, because of the power of his training in previous lives and the blessings of the gurus and Three Jewels, he was able to understand the textual meaning of scriptures.

When you read the liberation stories of Mikyö Dorje, some people would criticize him because he spent so much time reading all these texts and taking notes about issues. Others would ask, “What point is there to doing this?”

Some people in his entourage thought, “We are staying here in Ütsang so he can, without any benefit, read texts, take notes about issues, and edit carefully, but there are few people who make offerings. Instead of toughing it out here, it would be better to go a place like Kham where it would be as if food and drink showered on them like rain and he could have tens of thousands of followers? The way His Holiness does it is like a child’s game,” they thought. There were people with such wrong thoughts who denigrated him. In particular, most of the students and entourage who liked material things did not stay with him in Ütsang, but went off to their own homelands where they busied themselves with worldly concerns and gaining food tainted with misdeeds.

Mikyö Dorje would never denigrate them; instead, he would give them as many gifts as he could before sending them off. On the one hand, it is depressing because the student is giving up the guru. But, the way Mikyö Dorje studied texts and subsequently gave us the scriptures, opens up the eye of prajna for everyone. This is all due to Mikyö Dorje’s kindness. His Holiness relayed how Gyaltsab Rinpoche had noted to him, “If we look at how Mikyö Dorje went through a hard time, we should really rejoice in it.”

In brief, no matter what task or action Mikyö Dorje undertook, he did not engage in it with any ties of selfishness or the eight worldly concerns. Instead, he solely had pure intentions and actions to benefit the teachings and beings. Due to this, sometimes he would say things such as this:

“There is no one worse or more obscure than me.” He also said, “Just as Lord Götsangpa said, I have undergone all the hardship, so it is nice for all of you who place your hopes in me. Supplicate me, and follow my example, and I will not deceive you.” In this way, he gave them the great relief of fearlessness.

Part Two: Vegetarianism and the Environment

The Karmapa then continued his discussion on meat from the previous days’ teaching. Today, he put an emphasis on how animal agriculture and husbandry has great detrimental effects on land and water environments. His Holiness distilled the main points regarding the effects on oceans and forests.

Regarding oceans, His Holiness noted:

We catch between approximately ninety and one hundred million tons of fish. This includes 2.7 trillion living animals.” This is such an incredibly huge number of animals caught from the ocean each year. “There is a danger that by the year 2048, there will be no fish left to catch in the oceans,” he said. When you are fishing, if you catch a pound of fish, you are also catching so many other types of marine species. While you have the pound you wanted to catch, the others are discarded carelessly. Most of them die at that time. Every year forty percent of fish caught in the ocean are just wasted and are discarded. In terms of kilos, it is probably twenty-eight billion kilos of fish which are just thrown away. This figure is really scary. And, this is only fish. There are shrimp and other types of seafood, but it is really difficult to account for all the other sentient beings.

When we talk about animal agriculture or husbandry, in terms of forests, there is also great detriment. The largest forest in the world is the Amazon. Because of livestock production, over ninety percent of the Amazon Rainforest has been destroyed. In each second, between an acre and two acres is destroyed and converted to plant crops to feed cattle. Due to destruction of the forest, many different plants, animals, insects, and so forth go extinct every day. Not only do one hundred and thirty seven different specifies go extinct every day, but also due to livestock production, one hundred and thirty six million acres of the world’s forests have been destroyed.

His Holiness then distinguished between nomadic and commercial livestock production. He clarified that there are traditional ways of raising animals in the Himalayas which are quite distinct from commercial animal husbandry. The animals in Tibet must think they have been reborn in the pure realm of Sukhavati. Nomads only raise enough meat for a family in accord with what is needed for one’s life – slaughtering one yak will last for one year. Current livestock production, however, is quite different. It is only a business where the focus is on reducing expenses while selling larger quantities in order to get bigger and better meat. Since the emphasis is on production, it is significantly more dangerous and destructive than traditional ways of meat production.

His Holiness highlighted the correlation between taking up vegetarian or vegan diets as a means for environmental sustainability. First, His Holiness clarified distinctions between vegetarianism, not eating meat, and veganism, not taking or using produce from an animal. His Holiness emphasized that a single vegan can reduce water usage throughout the world by five thousand liters and twenty kilos of grains. Such a person protects thirty square feet of forest land by not eating any animal products. They can also decrease nine kilograms of carbon dioxide emissions and protect the life of one animal. By this person being vegan every day, the benefit and reduction in harm is that great. If we are vegan, then it is an even greater benefit to the world. His Holiness clarified, “The choices a single person makes definitely have a result and a connection to what happens in the world.”

His Holiness also gave several examples and resources for challenging common notions that eating meat is a source a strength. For example, the 2018 documentary about vegetarianism, The Game Changers, illustrates the health risks of eating meat from livestock production including: inflammatory diseases, heart disease, and cancer among others. Per this documentary, the research suggests that a vegetarian diet reduces heath risks and actually increases your brain power. Through examples of ancient Rome to contemporary Olympic athletes, the documentary demonstrates the numerous benefits of vegetarianism. For instance, many Roman gladiators were vegetarian and unbeatable due to their diet. Other examples included the champion ultra-marathoner Scott Jurek who linked his achievements to his vegetarianism, and nine-times Olympic gold medalist, Carl Lewis, who won track and field events between1984–1996. Lewis was the first person to break the ten-second barrier for running one-hundred meters. He is also vegetarian and was listed as one of the strongest men in the world at the age of thirty.

His Holiness spoke of the idiom, “strong as an ox.” Using this example, His Holiness reminded us that even these animals such as oxen and gorillas, known for their strength, eat vegetarian diets and get all their protein from plant sources.

He also emphasized the importance of nutrition. Because of the number of monastics in the monasteries, it is important to pay attention to whether the food is good and nutritious. The Karmapa mentioned that he had been vegetarian for ten years. Since becoming a vegetarian, he pays a lot more attention to the nutrition in the food eats. In fact, he has been learning how to cook. He joked that when he returns to India, he will be able to hold a competition with the cooks and nyerpas [the storekeepers who buy food].

His Holiness ended with some kind and encouraging advice:

When we talk about giving up meat, there is no need to worry. When I say it is important to not eat meat, we think it is important to not eat meat. But that is not the case. What I am saying is that if we cannot give up meat entirely, that is okay. But, if we can do something to reduce eating meat, then that is okay too. We just need to do what we can to decrease the amount of meat we eat.

In conclusion, His Holiness advised that vegetarianism should neither be a debate nor complicated, “If we make something easy into being difficult, there is no point.” In brief, when we talk about giving up meat or being vegetarian, it should be in a measured way. We should think carefully about what we want to do and gradually put it into practice. Instead of thinking, the guru or the scientist said this, we should examine it for ourselves, think about it well, and take our time.

Click the photo to view photo album: